Jack and Liv, two Midwestern homesteaders and Bitcoiners, discuss their farm, food health and how Bitcoiners inherently understand symbiosis.

This edition of the “Bitcoin Homesteaders” series brings you a conversation with Jack and Liv, homesteaders in the Midwest growing some of the best produce I’ve ever tasted. Having lived and traveled in Europe, we cover the differences in the two food systems and the impact on health.

We also discussed how they’re tackling the struggle of looking for suitable land, and the many tactics they’re using to maximize yield from their crops. Finally, Liv and Jack gave their two cents on why Bitcoiners naturally understand the benefits of homesteading and growing your own food.

For more about the homestead, you can follow Liv on Twitter at @LivChevre. For thoughts on Bitcoin from Jack, follow @JackyHODL. I hope you enjoy this conversation!

Sidd: Could you give me an overview of your homestead right now? When did you start, and what are you doing on the land you have?

Jack: So, let’s take it one step further back. We were over in Europe before, where my wife Liv is from, and we saw some things we didn’t like on the horizon. To protect ourselves a bit more, we decided to plant a flag in the U.S. as well, where I’m from.

We are now on my parents’ property, which has at least enough land to feed a family on. We’re running our homestead here while we wait for the housing market to correct itself and prices to come down.

My dad started multiple gardens on this land with a bunch of fruit trees and chickens. My wife and I brought in some youthful energy to do what my aging dad hasn’t been able to do: clean up these gardens and really make this place not just exist but thrive. I have a full-time fiat job, but Liv has been able to weed and attend to the gardens such that we’re producing much more than my dad is used to. We also started incubating chickens and doubled the amount of chickens quickly.

Liv: We had about 90 chickens, but going into winter we butchered about 35 of those so we’re now at 55. We also have bees.

Jack: We’ve been able to secure our food with just our land. We end up canning and preserving a lot of the vegetables, and the eggs just keep coming. We try to sell any excess that we have, or we put it back into the farm in the form of chicken feed or whatnot.

The latest project we’ve been working on since the gardens are finished for the season is designing a custom shed. We wanted an Amish-style shed that we can live in if necessary, so we contracted a builder who uses all natural materials and shipped right to the property. We tried to make that as off-grid as possible.

Let’s say electricity gets cut off: We have this old, 1918 wood-burning oven that we’ve put in the shed. That will allow us to cook and heat the home. We also want to run a water pipe through it so we can get hot water.

Eventually, we’ll set up a water-collection system there and put up some solar or other off-grid energy. The idea is that when we do find land, we can just scoop the structure right back up and move it over to the new property.

As far as how we got here, it involves a lot of education and learning from people close to you. Karl is one of those people we’ve built a relationship with who can help us out. We buy things from each other in bitcoin.

There is a little bitcoin circular economy developing in our area, coordinated through local Bitcoin meetups. There’s a builder in those circles who offered to lend us equipment for any builds we do, we can buy lamb from Karl and we can trade or sell the honey and other things we’re producing. And all of this is happening around Bitcoin meetups.

I went to a Bitcoin meetup a few hours away from me and found people selling milk, goat cheese and all sorts of produce. I was pretty impressed by that.

And so, if things do turn for the worst, we feel we can rely on that local community.

We’re not just sharing the resources that we’ve grown, we also are able to share the knowledge that we’ve acquired. Our Bitcoin community is able to exchange knowledge on how to raise bees, chickens or sheep, and how to install and run solar. Karl talked at a recent meetup about his experiences homesteading for six years now, and a lot of people were very interested in how they can apply those ideas in a more urban environment.

Sidd: Liv, what has your experience been on the homestead?

Liv: What I like about homesteading is it is a generational project. I’ve learned gardening in Europe from childhood onwards, as well as how to preserve and can things. My father-in-law taught me more ways of preserving things, and also how to save the seeds. My aunt just recently helped me with tips on how to harvest very small dill seeds. We tried making sauerkraut this year — it failed, but it was a good learning experience.

Saving high-quality seeds is also a big thing for us. All our seeds are non-GMO and untreated. I save, organize and label all our seeds in different envelopes.

As for recent work on the garden, we just finished preparing for the next growing season by spreading chicken poop on the fields to fertilize them. We also learned that we can leave pepper plants in the ground if we cut off the top of the plant and cover the stems with plastic — so we did that.

Jack: The seed saving is an important point. I think most people, come springtime, just buy seeds from a store. However, if there’s a shortage of seeds, you’re not able to grow again. So we learned from my dad to keep the seeds from our crops.

Sidd: What’s the process to get seeds, from your own plants or elsewhere?

Liv: We buy from a company called Seed Savers Exchange, which classifies if they are in any way treated or modified. When we harvest our own seeds, it depends on the plant. Tomatoes and okra are very easy to get seeds from. Swiss chard and kale, much harder — I don’t know how they produce seeds.

Sometimes we let the vegetable or fruit go past the point of being able to eat to see if it produces lots of seeds. We were lucky with radishes recently — two or three plants that we forgot to harvest produced around 200 seeds. So, we specifically let a couple of plants continue on past the point of being able to eat them just for that reason.

Sidd: Do you produce everything that you need to live right now? Will you make it through the winter off just what you preserved?

Liv: We canned a lot of vegetables and also have more in the freezer along with 35 chickens and a lamb we bought from Karl. However, it’s our first year here, so I don’t know how far we will get. Plus, starting in the spring, we cannot just start eating right away — the food will take some time to grow into the summer before we can harvest it.

Swiss chard is one of my favorite plants for consistent yield. It’s the most simple way of growing your own food. You grow it once, and you can keep cutting the leaves off and eating them. They will just grow again. I also was surprised that I could harvest broccoli until the middle of December. Kale and salsify as well — we still have it in the garden now. We just cover the produce with a clear plastic sheet, like a cheap greenhouse, to keep the snow off.

What we’ve found is that if we use permaculture-based methods, you can let the garden do whatever it wants. It will grow on its own and thrive. Otherwise you are dragging the water hose around when it hasn’t rained for three days just to keep things alive. If you get a good system going, it’s less and less work over time.

Sidd: Do you have any other livestock aside from the chickens?

Jack: Just the chickens for now. Our freezer is full of those chickens we butchered in the fall, but we’ve been digging into the lamb harder. If we run out, we could buy two for next year. Hopefully by this time next year, we’ll have our own sheep.

I like how Karl talks about having live sheep — they’re like a battery that stores potential energy for later. The animal is eating the grass and everything, storing that energy, and at any point in time when he needs the meat, he can slaughter it. Once it’s butchered and in the freezer, you’ve got to make sure the electricity is still running because you can’t eat it all at one point in time. Live animals require upkeep but in a different way.

So, we’re looking forward to getting some ruminants. Our idea is either goats or sheep, or a couple of both. We’re hoping to grab one of Karl’s pregnant sheep soon. That’s another example of the benefit of this circular economy and network of Bitcoiners.

Sidd: Speaking of the work on the homestead, what kind of labor is involved for you now, and how does that change across the seasons?

Jack: Right now in the winter, we’re focusing on building. A lot of woodworking. Once it starts to get warmer we’ll start to prepare the gardens, and a lot more physical work happens. The tractor is necessary. We’re fortunate that over the years my dad has collected an abundance of tools and machines that are so useful.

How many tools you involve all depends on how much work you want to put in and what you want to invest. Before we moved in, my dad was casually tending to his gardens on his own, just planting things whenever he wanted. Now that we’re here, we are more intentionally tending to it with more tools. Yields are up as a result. That’s thanks to Liv, who can spend all day weeding and watering while I’m at my fiat job. If we both had a nine to five, we couldn’t do a fraction of what we accomplished in the last year.

Liv: Getting back to the seasonal labor, around February or March we start to put seeds in soil and keep them inside while they sprout. Once we move them outside, we weed and water when we need to all summer. I also spend a lot of time just digging through the soil to disturb the weeds. If the weeds are always kept down, they can’t keep up with the plants. This is what you want. Another big task during the summertime is to breed the chickens. We’re thinking of starting the breeding process in mid-March, so that the eggs have 21 days to hatch. Then we will keep them for 10 weeks in their own chick coop, until they’re ready to join the main flock.

Come fall, all the crops are there all of the sudden, and it’s time to harvest all we can. Then we freeze and preserve things, prepare the gardens for winter by digging through the soil to introduce some air into it, and get the chickens in the coop.

One interesting note is that throughout the seasons, you have to observe before you work. Observation is the most important part of growing a garden. For example, my father-in-law had planted a bunch of celery that I didn’t even notice as they were overrun with weeds. So I went out and weeded the whole field. However, the celery died. I think they couldn’t handle all the sun, and the weeds were actually giving them shade and a comfortable environment.

So that was a big mistake, but I learned through it.

Jack: One thing we missed is the bees. They can be a bit temperamental. Liv was talking about being in control of the entire environment until the crops are ready to take over on their own. You control the water, the seeds, the placement, the weeding until the crops are established and can go on their own.

With bees, it seems like nowadays human intervention, or beekeeping, is a necessity to protect and sustain the species. It didn’t used to be like that. As you probably know, there have been a lot of problems with bees over the last 20 years. I think pesticide is probably the biggest one, with monoculture agriculture being an assistant to that problem.

The fields around us are all growing the same things so the bees don’t have a really nutritious diet from a variety of plants. That’s one reason why we plant a lot of sunflowers every year. Pesticides are also a huge problem. If the wind happens to blow the wrong way while they’re spraying, that could be it for your hive for the year. Hives typically don’t last more than two years in our experience and from other beekeepers we’ve talked to. It seems the genetics in the bees are not very resilient anymore. Colonies are not reproducing and getting stronger throughout the years.

Sidd: You mentioned earlier that you’re looking for land. What exactly are you looking for when you’re evaluating land?

Jack: I think what’s most important is the surrounding land and the soil health. We’re in corn country here, growing for cattle or chicken feed. As a result, the farmers don’t care much about the quality of the food. It’s just a product to be grown, and they’re aiming for maximum yield. That means chemicals, pesticides, all of that.

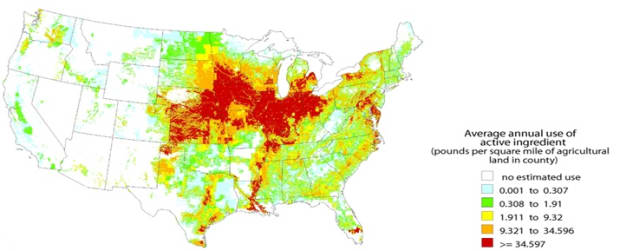

The problem as a neighbor is when the wind’s blowing the wrong way that can get into your house, on your land, into the water table of your well and more. If you look at a map of where these chemicals are used on food products, the Midwest is dark red.

That shows how poisoned our local food is. We’re trying to find a little pocket of nature that these companies and industries haven’t polluted. You can find that in the Northern Midwest. What is awesome about this area is the freshwater resources of the Great Lakes.

Even beyond agricultural pollution, there’s industrial pollution as well. Even next to a highway, you get brake and tire dust and exhaust fumes. That might seem paranoid, but at one point we also thought lead was fine and asbestos was the next great building material.

We’re looking into these chemicals as well with the structures we’re planning to build on our homestead. What are these products, are they carcinogenic or could they potentially be harmful? It’s incredible what they will sell at the Home Depot or whatever hardware store you’re getting materials from. They’re all treated, from wood to insulation. We’re trying to look forward and think about what products could be harmful in the future, just to be safe.

Sidd: When did you start to go down the Bitcoin rabbit hole? It sounds like both of you have this long history of anti-establishment thought. Did that play into your discovering of Bitcoin as well?

Jack: I think we might differ quite a bit on this. For me, personally, my dad always had me question everything — including authority — and taught me to verify things for myself. Probably in high school, I started thinking a bit more politically and was disgusted with our lack of options. I was introduced to Ron Paul, and thought there might be a third option where we don’t rely so much on the right or the left to fix our problems. We can actually make our own independent decisions. That’s where the rabbit hole started for me; a bit of Libertarian thinking.

I discovered Bitcoin in college through Reddit forums very early on, maybe in 2010 or 2011. However, computer science was never my strong suit and I was not technical enough to be able to really understand Bitcoin at that time. It sounded like a good idea, but I had not the slightest clue on how to acquire some even if I wanted to.

Year after year it just never died, and after the run up of 2017 I decided to at least get some skin in the game. I bought at the peak while living as a nomad in South America and held through that bear market. Thankfully I didn’t go all in, but I did put a lot of my travel fund in which made traveling hard for a while!

I kept slowly learning about it. When COVID came and central banks started talking about printing not hundreds of billions this time, but trillions, it clicked. I thought this had to be a problem for inflation, and Bitcoin with its limited supply was a no brainer. I felt the ship was sinking, it’s time to grab a lifeboat. In 2020 I had a lot of time to educate myself through podcasts, books, articles and the like.

For the past three years, I haven’t stopped consuming content, thinking about different aspects, and discussing with people. We started a Bitcoin meetup in our city, just so that we could have face-to-face conversations. Liv, what about you?

Liv: I studied psychology in Europe with a focus on behavioral economics. I learned about the incentives that led to the 2008 financial crash, and 2020 was a real case study in how irrational people actually are. At the same time, I had Jack, who would talk morning, day and night about Bitcoin! At the beginning, it was pretty intense.

However, what I observed during COVID got me on board. All the small and local businesses growing organic food were devastated because they couldn’t keep up with the regulations, while the big businesses thrived. So I started to become more interested in Bitcoin, in understanding what money is and the politics that can lie behind it.

And now, I’m convinced that this helps people because it gives us all a different perspective on life. Same as gardening. When you know what you grow, the work it takes, and the satisfaction of eating it, you are more sustainable. You try hard not to waste anything. It’s the same with money: The money you don’t earn, that’s printed out of thin air, is easy to spend. Truly scarce money makes you think harder about why you’re spending it.

I see a lot of people in the Bitcoin community have struggled in the past; but they change as they begin to understand the money they earn and store in bitcoin cannot be inflated away. They can think more long term, and having that kind of attitude and perspective on life is, I think, very important.

Sidd: Before we conclude, I’m curious about the differences in the food systems between America and Europe. Are there different regulations or practices that affect food quality?

Liv: So, I recently spoke with someone who worked in the food system about this topic, and he said there is really no organic certification here in America we can rely on to certify that a plant hasn’t been treated at all. In Europe there is a label called “Demeter,” which signifies biodynamic farming practices. These are truly untreated. If you haven’t implemented a permaculture system, you can’t keep up with the Demeter certification — it’s just too much work and cost if the land isn’t doing it for you.

Jack: Speaking of labels, I’ve noticed in both Bitcoin and farming that terms are very important. For example, take the term “tomato.” What that means to people is the GMO, pesticide-laden tomato on the grocery store shelf, whereas what I’m growing is an organic tomato. I think the tomatoes we’re growing should be simply tomatoes, and we add treatments and modifications to other kinds of tomatoes. Then there’s processed foods.

When you go through the middle aisles of the grocery store you can’t identify anything as actual food that you would grow in a field. And you wonder why we’ve got all these health issues as a society! This doesn’t happen if you get into the symbiosis of how the real world works, how nature actually works. You work with it, rather than trying to control it. That’s the whole permaculture idea.

In Bitcoin, we have something similar with terminology and control. For example, some government agencies want to label wallets as “unhosted” wallets. It’s just a wallet. The custodied wallet should have separate terminology, not the basic wallet you control yourself.

Our political system has tried to control money with the same results as trying to control food. If we just go back to obeying physics and mathematics with our money, we can design our world on that solid foundation instead of trying to intervene constantly and control the money. Ceding that control means markets can be in symbiosis more.

I think Bitcoiners and people who eat natural food understand that working with the natural cycle of things is in the long term a lot more sustainable, and just frankly better.

Liv: I think fear plays a big role in all the attempts to control as well. Like in food for example: If you sell your own eggs in front of your house, and one egg is bad and happens to get someone really sick, suddenly there’s a whole cascade of fear. That leads to a push to change the system so it prevents this. More and more control comes from those urges to prevent bad outcomes.

Jack: Texas Slim always says “return to the source of the seed” — it all starts from the ground, from the underlying mechanism. Bitcoin is that base layer a stable economic environment can be built on top of. Same thing on the farm. If your soil is bad, you can’t do anything. And same thing with yourself, your own health. If the gut you use to digest nutrients is bad, good luck. It’s going to be very hard.

Sidd: Last question: Do you have any advice for new homesteaders?

Jack: For anyone who has started or gone down the Bitcoin rabbit hole, remember how intimidating that was at the beginning. But you get through it — you buy some, you read more, you get a hardware wallet, you listen to podcasts. You just start, and keep asking questions as you go. Don’t overextend yourself. Even just growing from seed can be a bit difficult. Don’t go buy a 400-acre farm thinking you’ll be able to handle it, even if you have all that money. Take it easy. If you’re in an apartment with a balcony, buy a pot of soil and start a tomato plant or something simple. If you like spicy food, try some chilis.

Also, if you have a small backyard you can consider chickens. Two or three chickens and a small coop are easier to handle than you think. You can feed them grain from the store, and they’re fascinating to watch.

Just start, and as Liv said earlier: observe. Take the time to observe what you’re doing and what you’re growing. Also, start paying attention to what you’re consuming, even if you’re buying from the store. Just take that extra second to look at the ingredients and choose products that are simple. Pick the peanut butter that’s just peanuts, not a bunch of highly-treated oils and sugar.

Liv: Remember that you can eat more parts of the plant than you might think: for example, I’m boiling the leaves of beetroot, and they taste like spinach. Also, Swiss chard is easy to get started with. Grow it once and keep cutting leaves forever. If you want to cut down on the bitterness, boil it a bit. Salad lettuce on the other hand is very difficult to grow. It needs the right soil. So just try things and observe.

Having a community to learn from is important too. Through more experienced people you get hints and ideas on how to accomplish things. Due to differences in your climate or just your soil, almost nothing will work exactly as someone advises, so you’ll need to experiment on your own.

Most of all, just get started.

Sidd: Thank you so much for those words of wisdom and sharing all your experiences!

This is a guest post by Captain Sidd. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.