Company Name: Gridless

Founders: Janet Maingi, Erik Hersman and Philip Walton

Date Founded: August 2022

Location of Headquarters: United States | Operations in Kenya, Malawi and Zambia

Number of Employees: 10

Website: https://gridlesscompute.com/

Public or Private? Private

Gridless doesn’t just mine bitcoin — it helps to facilitate the electrification of rural Africa, which is notably improving the lives of those who previously either didn’t have access to power or couldn’t afford it.

Gridless’ co-founder Janet Maingi explained to Bitcoin Magazine how the company’s facilities, which are based in Kenya, Malawi and Zambia, have a win-win-win effect for the company itself, the Bitcoin network and the communities that benefit from Gridless’ operations.

“Our mission is to mine Bitcoin profitably,” Maingi told Bitcoin Magazine. “But as we do this, we also do two other things: we push electrification out to the edge in Africa and we decentralize the Bitcoin network, which has historically been very centralized to North America and China.”

In just over two years, Gridless has set a new standard for the type of impact a Bitcoin mining company can have, showing the world that Bitcoin mining can have a symbiotic relationship with the communities it touches and that it can be a catalyst for human flourishing.

I sat down with Maingi in person in Kenya after this year’s Africa Bitcoin Conference to discuss the work she does and the impact it has on the communities it reaches.

A transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows below.

Frank Corva: How does Gridless help to electrify Africa?

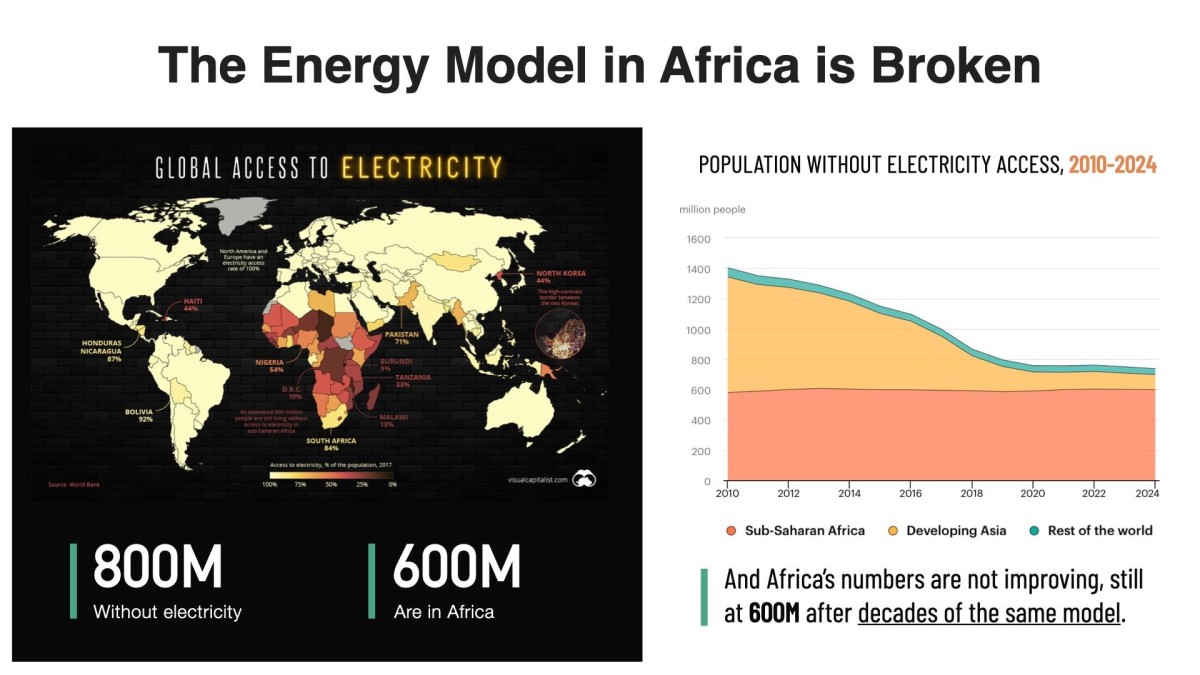

Janet Maingi: About 600 million Africans have no access to electricity. That’s about two-thirds of our population. The private sector has stepped in because the main grids do not reach everyone on the continent.

You’ll find that bigger cities like Nairobi or Mombasa have electricity, but if you go to rural Africa, people have no access to electricity because of distribution challenges.

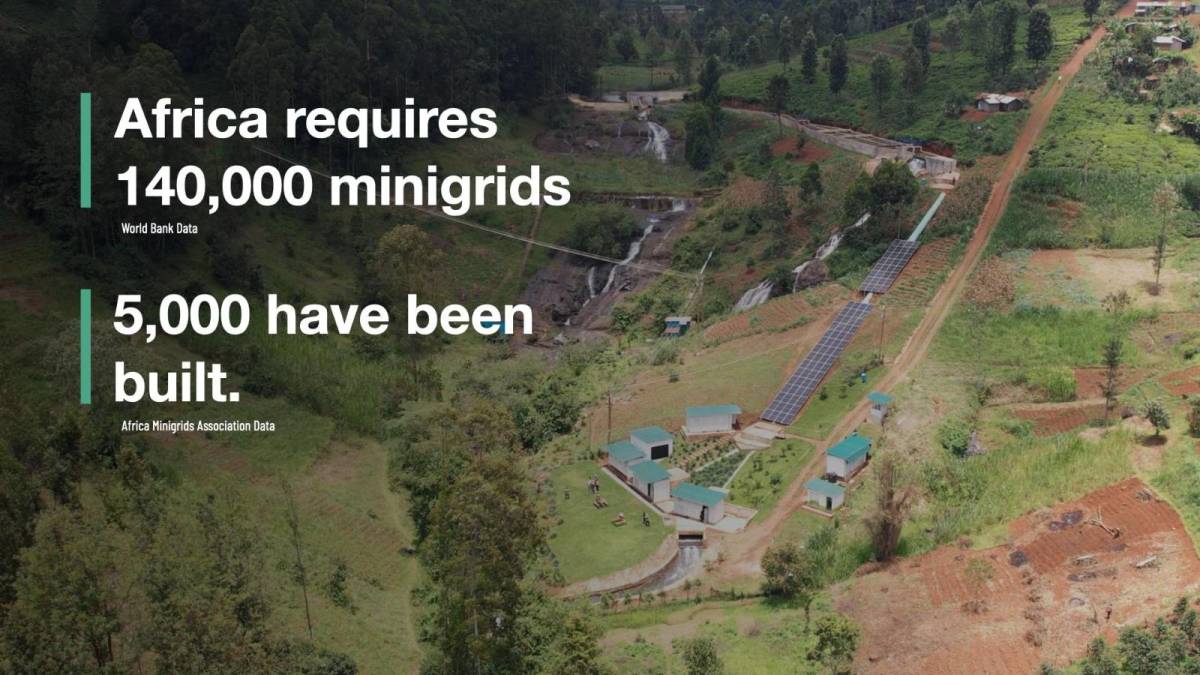

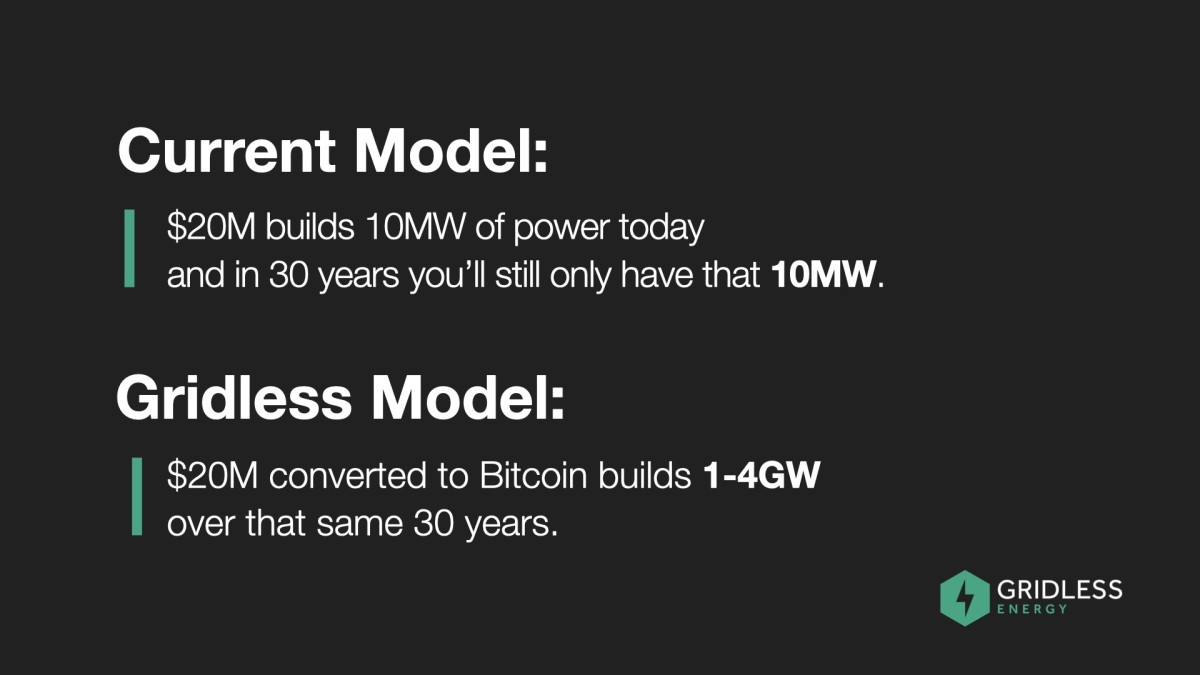

So, the private sector came and started setting up mini-grids. Private companies have done the best they can with these mini-grids. However, they’re very capital intensive, and so there are struggles with fundraising. And even when you actually get them set up, the consumers around your area might not be very wealthy. They’re just living day-to-day. They may have to consider “Do I need electricity or do I need food?”

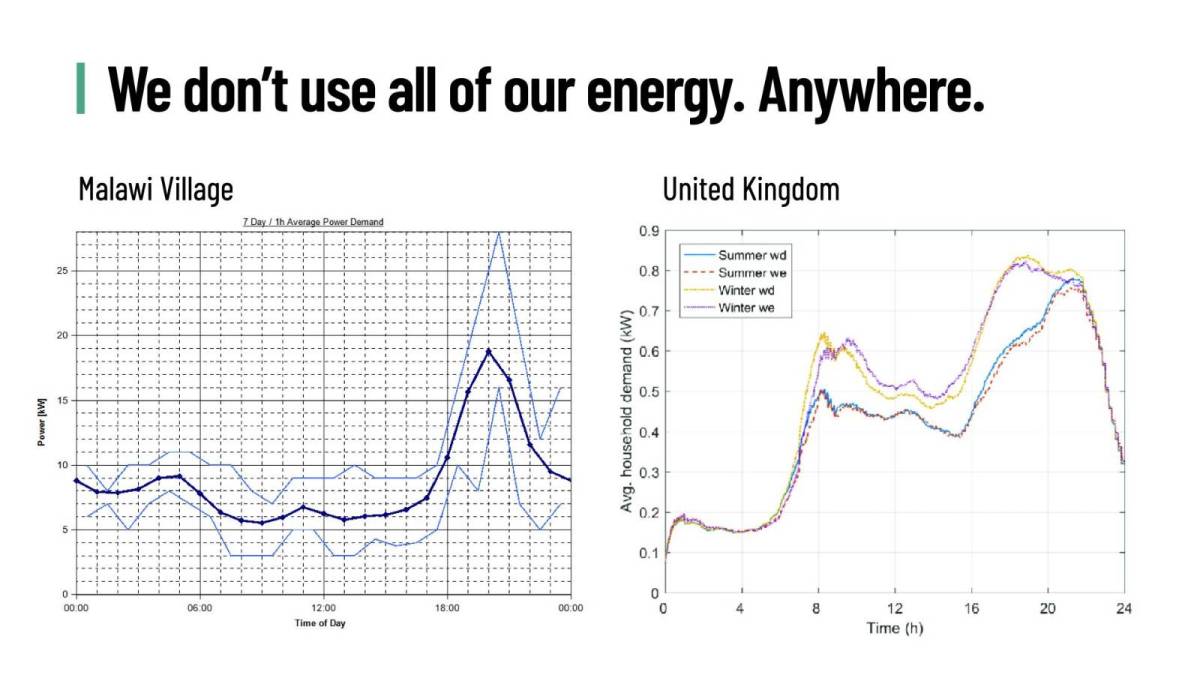

The companies that construct the mini-grids build power plants that use hydro energy. Let’s say they want to build one that produces one megawatt of energy, but the community only ends up using 200 kilowatts. There’s 800 kilowatts that they generated from the river, but for that 800 kilowatts, they get zero shillings, zero dollars, zero anything.

So, we at Gridless come in and say “That electricity that you’re not able to send to anyone, is what we want.” That’s what you call stranded power or wasted energy, and it’s what we want. So, we become your buyer of last resort.

We come and create an agreement to use that extra electricity, and from a revenue sharing perspective, we work together. It’s a win-win situation. Our data centers use that electricity to mine bitcoin.

But then the catalyzing of electrification comes in. When we’ve used that electricity, it’s become a source of revenue for the energy power plant. They were not making money on that electricity previously, and now they’re profiting from it.

What have we seen as the effect? One, they are able to extend their reach, to distribute electricity further. And secondly, some of them have been able to actually lower their prices. So, consumers who are within their reach but wouldn’t use the electricity because of the cost are suddenly saying, “Hey, hook me up. I can afford to pay for this now.”

Corva: So, in a sense, you’re subsidizing the rate of electricity.

Maingi: Yes, because we come in and use this power, the energy generator is able to give better prices and increase its reach. So, again, what does this mean? More homes getting lit, more small enterprises getting electricity, more factories getting powered and more health centers getting electricity. You can now imagine the upward spiral effect.

However, the challenge is that doing business in Africa is like an extreme sport.

Corva: Why is that?

Maingi: So, let’s start with just getting the equipment. The mining machines come from China, either from Bitmain or MicroBT, or you’ll get them from a company in the U.S., and the process of getting them into Africa can be painful.

We received a batch that came from the U.S. and it took us 60 something days just to get them into the country. This is from putting them on a ship to getting them here. This doesn’t include figuring out the logistics around getting the miners on site and going through pre-shipment inspection to make sure that they meet the Kenyan standards.

It’s a process that takes almost 120 days from start to end. If you’re running a business, and it takes you 120 days to get your product on the ground, it’s painful.

Secondly, these machines are designed to work very well in China or the U.S.

Conditions in Africa are different, though.

Corva: Does this have anything to do with air quality?

Maingi: Air quality, dust, heat. In Kenya, average temperatures range from 20 to 40 degrees Celsius. So, when you power those machines in an environment where the average temperature is 30 degrees Celsius, you can imagine the heat that they have to deal with.

And then there’s dust. When you get a pre-fitted container from China or somewhere, you discover that the designers just focus on inflow and outflow. But we realized we have issues with dust, so we have to put dust filters on the machines.

And then, in 2022, we learned when we set up the first site that, because of the lights on the miners, they attracted bugs. During the rainy season, the bugs could see the lights and flew into the fans and got mashed up — something nobody thought about.

Lastly, the containers initially were going to cost us $100,000 each, which was too much for us to be profitable. The math didn’t math, as we say. So, we sat down and designed our own container.

Corva: Amazing.

Maingi: Right? And that’s what we’ve been deploying at a quarter of the price. And then the advantage that came with being made in Kenya has allowed us to get passage through the COMESA (Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa) region, without having to pay extra duties or taxes because it’s recognized as a COMESA product.

That also helped because, being made in Kenya, it’s very easy for us to move the containers around the COMESA region without having to pay extra taxes. We get a tax exemption. Even if the containers from China made sense, if we brought them to Kenya and I had to move them to Uganda, I would have to pay taxes to Uganda, too.

Any country you move foreign products to, you have to pay taxes again. So, it’s been hard, but good solutions have come out of the difficulties.

Have you heard of GAMA, the Green Africa Mining Alliance?

Corva: Yes.

Maingi: During the first Africa Bitcoin Mining Summit last year, we released a blueprint of the container we designed. So, anyone who wants to use it to build their own container using our blueprint can feel free to do so.

Where you need our support, we’ll be ready to guide you. That’s the whole thing about GAMA — How do we exploit our synergies? How do we benefit from one another? How do we find a young lady who wants to start mining and walk her through the journey of getting started?

Corva: Incredible. I want to go back to electrification in Africa. You mentioned earlier that you wanted to share some numbers.

Maingi: What I was saying is that there’s a ripple effect when we partner with the energy generator. We’ve been able to see more homes or households getting connections.

If you’ve been in rural Kenya or Africa, then you understand how one bulb can transform a life. I’ll use the example of children coming home from school. They have assignments and use these tiny paraffin lamps to study. The fumes from them are horrible for their health. But this is a child for whom there’s no plan B. The teacher expects this child to come back to school with her assignments completed. Not having electricity is not an excuse.

A guy once told me that sometimes, when his daughter is busy doing an assignment, the paraffin runs out. When the nearest gas station is almost four miles away, who is going to go and look for paraffin at that time? Nobody. Tough luck.

So, the child gets to school and is either in trouble because she didn’t do her assignments or is now lagging behind because now those quote unquote “are yout personal problems.” Because of that one bulb they now have, he was like, “My daughter is performing so well in school.” Then, health wise, all these visits they used to make to the hospital because she was breathing in the paraffin fumes no longer happen.

Corva: It seems you want to make my cry.

Maingi: No, there’s no crying. (Author’s note: This woman doesn’t play.) It’s a reality.

Then, in Zambia, I remember talking to women who were talking about childhood vaccinations. Between zero and three years, there are certain vaccinations recommended by the WHO that your kid needs to get — measles, polio, etc. — but the nearest health center that has them sometimes isn’t close.

So, you do your math, and you’re like, “I can’t afford bus fare to do this.” And so this disease sounds more serious, I’ll get my child the vaccination for that one, while this one I’ll pass on. But really all of them are important for children.

Now, Gridless is coming into Malawi and getting electricity providers to connect more homes in the Bondo area. Health centers are getting powered on, so more vaccines are available in more local health centers.

While before you used to say “Polio sounds serious, I’ll get my child that vaccine, but with measles, I don’t know who has died of that recently, so maybe, I won’t get my child that one,” now more people can get it.

Now, we will have a young generation who, we believe, as we keep doing this, is going to thrive. They’re going to grow. You’ll possibly get rid of childhood mortalities because these rural areas get electrified.

Corva: And bringing energy to these regions also helps support livelihoods I assume.

Maingi: Yes, of course. There’s a tea factory in Muranga, Kenya, which is in the highlands.

We partnered with the energy generator in the area and they were able to give the factory power. Now, their facilities are able to support the tea factory, which has two benefits: tea farmers can bring their tea to the factory, which means it doesn’t spoil on the farms because they can’t get it to point B in time and more employment has also been created just by that tea factory becoming an electrified space.

We keep saying why we know this will make a difference is because energy is a base of human progress.

Corva: There’s no such thing as an energy poor country that’s rich.

Maingi: If you look at the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, it used to go food, shelter, clothing, but I put energy there. Energy is a basic need. It’s a must have for anybody to actually be allowed to live a decent life. For people to make a decent living, energy has to be in that math.

Corva: Is it true that you’ve recently created software that helps with energy demand response?

Maingi: Yes. We realized that we need to get more proactive in creating real-time demand response. Before, we were either reacting too late or too early to the power available.

Remember we’re the buyer of last resort, so communities come first and small businesses come second. For us to be able to live up to that promise, we had to make sure we weren’t sucking in electricity that was required by somebody else at that time.

So, let me paint a picture. In normal households, people wake up at 6 a.m., so there’s a surge of electricity. At that stage, our software gets a signal and reduces our consumption to meet the demand needed by the grid. Then, at 8 a.m., everybody goes to school and switches off their lights and there’s too much electricity in the grid. That’s when we power more mining machines.

We get the signal, power more machines, suck in the electricity and keep on going until maybe 6 p.m. when people have gotten back home and they need the electricity. Gridless turns down their machines and returns the electricity.

At 10 p.m. they all go to bed, and we power up more machines. This is all done with software we developed internally called Gridless OS. It allows for real-time demand response. It makes it so everybody gets what they need, and it stabilizes the grid.

Corva: Are you setting certain standards with Gridless that others are following in Africa or in other parts of the world?

Maingi: It’s set a trend that people are following. Sometimes you go to conferences and people keep referring to Gridless. That’s when you realize, “My God, this thing is bigger than we thought.” And so you start to understand how this has made a difference, that it doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

At the end of the day, everyone has different ways of mining bitcoin, and there’s a positive impact to the community whichever way you do it. Look at Bigblock Datacenter — Sebastian Gouspillou in the Congo — where they’re using the heat to dry cocoa for chocolate they sell. Think of what that has created for that economy.

Corva: I think Sebastian brought me to tears when I met him, too.

Maingi: What’s exciting for us and other players within this space is that we are the ones who understand our problems, and it’s exciting to see African companies deciding “Not only will I mine bitcoin profitably and decentralize the network, but there’ll be some benefit to our community, as well.”